The fundamental ideas of Alexander Dalgarno revolutionised the way science comprehends the cosmos. His pioneering research into atomic and molecular processes laid the groundwork for modern astrophysics, atmospheric science, and theoretical chemistry. It was through his prolific work that the world first truly grasped the unity between the microscopic and the infinite vastness of the Universe. Read more on london-future.

Alexander Dalgarno’s Early Life and Journey into Astronomy

Alexander Dalgarno was born on 5th January 1928, in London. He spent his childhood in the Winchmore Hill area, where he showed an early flair for the exact sciences. Despite some initial difficulties with the 11-Plus examination, his determination to learn never wavered. In 1945, he enrolled in University College London (UCL), where he excelled not only as a gifted student, but also as an active participant in university life, serving on the student council and as the treasurer of the UCL football club.

After successfully defending his doctoral thesis in 1951, Alexander Dalgarno was invited to join the Department of Applied Mathematics at Queen’s University Belfast. There, he began a crucial collaboration with the distinguished physicist, Sir David Bates. A 1954 visit to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) proved to be a turning point in the young scientist’s career. His encounter with MIT’s electronic computing machines inspired him to establish a similar technical hub in Belfast. It was there that Dalgarno performed his initial calculations of the interaction potentials between a hydrogen atom (H) and a negative hydrogen ion (H⁻). These calculations later became fundamental to research on charge-transfer processes in hydrogen gases—a mechanism key to understanding cosmic environments.

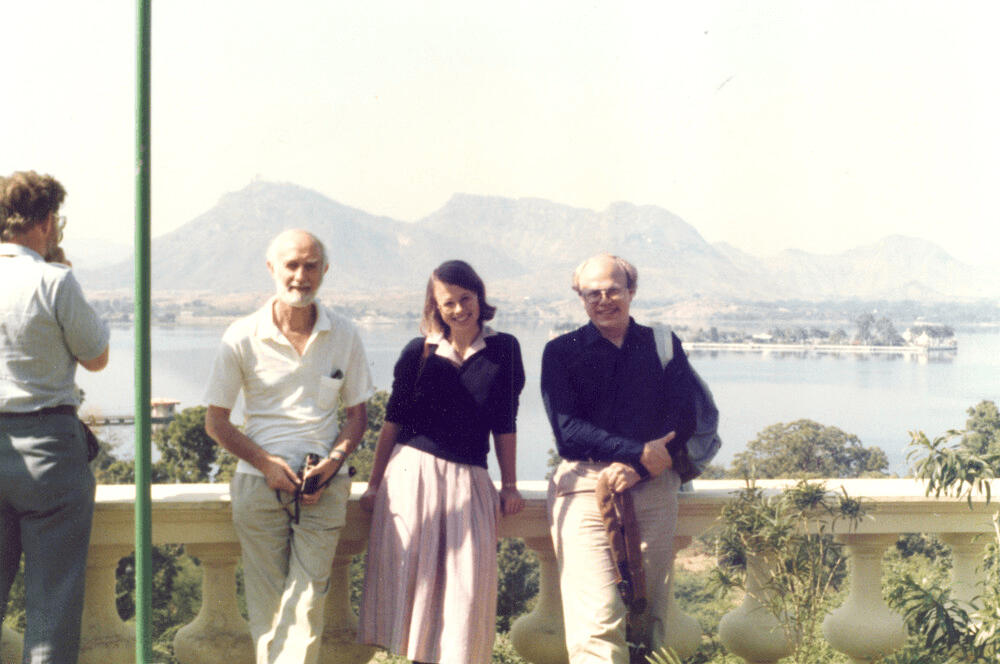

In 1967, Alexander Dalgarno moved to the United States, taking up a professorship at Harvard University and a research post at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was here that he became one of the first to focus on integrating atomic and molecular physics with astrophysics. Furthermore, the scientist made a significant contribution to atmospheric sciences. Notably, his studies on the photodissociation of hydrogen molecules (H₂) helped to explain processes occurring in the atmosphere of Venus. By the end of the 1970s, the majority of his work centred on interstellar clouds at temperatures below 100 K.

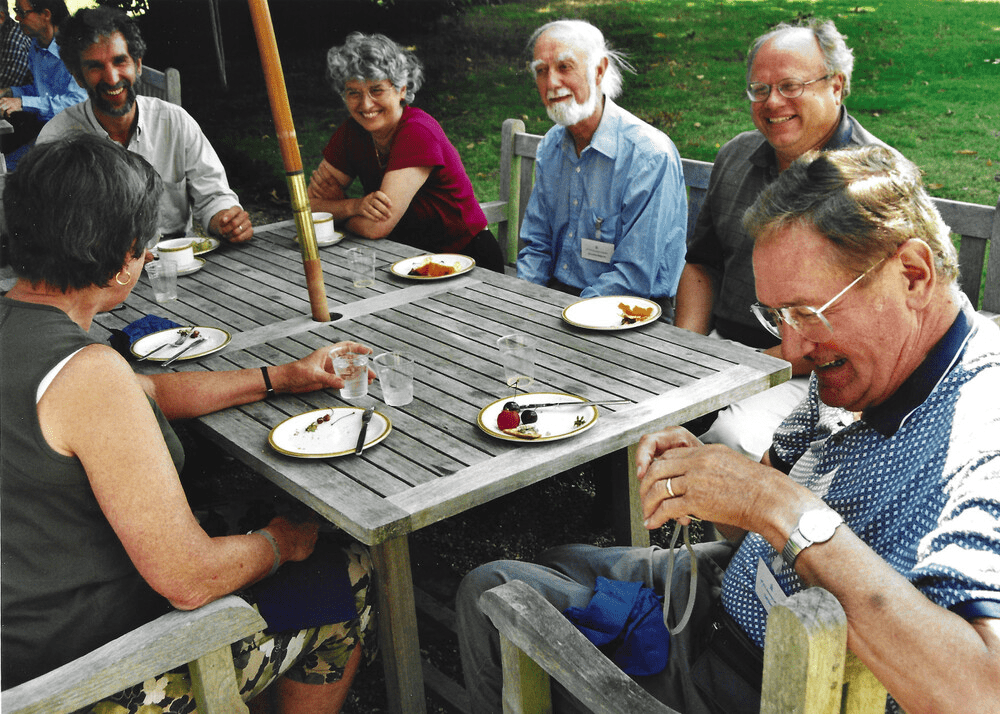

During the 1980s, Alexander Dalgarno noticed a systemic gap in American education. He was concerned that most US university physics departments were not giving enough attention to theoretical research in atomic, molecular, and optical physics. His proposal to the US National Science Foundation (NSF) led to the establishment of the Institute for Theoretical Atomic and Molecular Physics (ITAMP). Thus, in November 1988, he became its inaugural director. Under his leadership, ITAMP quickly transformed into a leading international centre for research into light-matter interactions, fundamental collision physics, and quantum processes. All the while, he continued to publish actively, mentor young researchers, and make substantial contributions to astrophysics.

When ITAMP celebrated its twentieth anniversary in November 2008, Alexander Dalgarno remained its spiritual inspiration and scientific authority. His final work, which explored the subtle quantum effects associated with the cooling of silver atoms in magneto-optical traps, was included in the proceedings of the International Conference on Photonic, Electronic and Atomic Collisions. On 9th April 2015, after a long struggle with Parkinson’s disease, Alexander Dalgarno passed away in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Recognition and the Significance of Alexander Dalgarno’s Scientific Work

Alexander Dalgarno left an indelible mark on global science as one of the most distinguished theorists of the 20th century. One of his most crucial achievements was the founding of molecular astrophysics as a distinct intellectual discipline. He was the first to systematically blend quantum theory, plasma physics, and observational astronomy, demonstrating how the behaviour of individual particles dictates the evolution of interstellar clouds, planetary atmospheres, and stellar systems. He also developed fundamental theoretical approaches that became the bedrock for modern computational models in space physics. For his life’s work, the scientist was honoured with the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society, the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Physics, and an Honorary Doctorate from Queen’s University Belfast.